Sabiah Mandaeans

Authors: Johann Hafner and Adad Zaya

Foundation and History

Mandaeans (mandajî means “the knowing ones”) spoke of themselves as Nasurajî/Nazoreans in early times, and are called Sabians (meaning “the baptized”) by Muslims.[1] This religion is probably a successor of baptismal movements of the first century CE.

Their earliest texts were written as early as the third century BCE. They were collected in the Ginzâ (treasure), which contains prescriptions for earthly life and descriptions of the soul’s descent into Adam; the Book of John from the Bible with teachings ascribed to John the Baptist, and the Kolasta (meaning praise in English), which is a collection of hymns, prayers, baptismal, funeral and wedding ceremonies.[2] Its main theology resembles the Gnostic myths of the second century: God (called “The Great Living God” – haijî rabbi) reigns in the world of light (located in the north) and is surrounded by beings of light. After several emanations a lower God “ptahil” or “rûhâ” creates the material world of darkness and demons, located in the south. The first human, Adam, consists of a soul that descends from the world of light and is trapped in his body created by Ptahil. For salvation, a messenger called “Manda d-Hayyi” (knowledge of life in English)[3] is sent. He helps to free the souls from the material world and their return through planetary spheres back to light. This is ritually performed by a – sometimes weekly – baptism through immersion and an anointing with oil.[4] It is believed that the knowledge about the truth was passed from God to Adam, Seth (in Mandiac “shetel”), Sem (“Sam bin Noah”) and finally John the Baptist (“Yahya bin Zekaria”).[5]

Mandeans lived mainly in the ancient Mesopotamia, currently the southern parts of Iraq and Iran. As rivers are considered an important factor for practicing Mandaean religious rituals, their communities were usually located in places near rivers or in the marshes. Their population in Iraq decreased from approximately 60,000 to fewer than 5,000 after 2003 – when the US invaded Iraq. The massacres and persecution conducted by the recent extremist Islamic groups against the Mandaeans have pushed them to emigrate to other countries, hence distributing their communities in diaspora. Nowadays, their number does not exceed 100,000 worldwide, living in Europe, America, Australia and other countries.[6]

The community in Erbil does not possess any chronicles, but relies on oral tradition. According to Khalid Roomi, chairman of the parish leadership committee, the Mandaean religion is one of the world’s oldest, originating in Sumerian culture, because gold and jewelry played as prominent a role in Sumer as they do among the Mandaeans today.[7] Roomi admits that there is no archaeological evidence of its presence in the Middle East before the arrival of Islam. In the 20th century, around 1,500 people fled from different countries – mostly from Baghdad and the Kerbela region – to Erbil and formed a new community. After the breakdown of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, another wave of refugees from southern Iraq arrived in Kurdistan, settling in Erbil, Suleimani, and Dohuk.[8]

During the same period, the vast majority of Mandaeans left the country. Before 2003, about 75,000 of them lived in Iraq, while only 15,000 returned in 2019.[9]

[1] It is not clear if the Sabians mentioned in Sura 2,62; 5,69; 22,17 (Ṣābiʾūn) as one of the “peoples of the book” refers to the Mandaeans. For sure the Sabians are not identical with the Sabeans (members of the south Arabian kingdom of Saba/Sheba).

[2] Ethel S. Drower (transl.): Mandaeans. Liturgy and Ritual. The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans (Leiden: Brill 1959); Mark Lidbarski, Das Johannesbuch der Mandäer (Gießen: Töpelmann 1915); Mandäische Liturgien, Berlin: Weidmann 1920; Ginza, Der Schatz oder Das große Buch der Mandäer (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1925).

[3] Drower, E. S. explains in her book, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1937), that Manda, in Mandaic, refers to a dwelling or cult-hut.In some contexts it means knowledge, i.e. manda dehaijî, 10-11.

[4] Kurth Rudolph, Die Gnosis. Wesen und Geschichte einer spätantiken Religion (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1994), 388.

[5] “Mandean Sabians,” (brochure handed out by the Erbil community 2016), 2. In other versions, Abel (“Hibil”) and Henoch (“Anôsh”) also transmit salvation.

[6] Al-Haydar, N. “Sabea Mandaeans,” a brochure issued by the community in 2016.

[7] “According to Arabic research, we are more than 4,000 years old.” Interview with Khalid A. Roomi, the chairman of the parish leadership committee, on November 12, 2020. The same claim is made in the brochure the community printed. Yet, this is speculation that cannot be proven by a chain of historical evidence. The similarity of rituals and symbols in 2000 BCE with rituals and symbols in 2000 CE only shows that there is a pool of commonalities, not that there is a tradition.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

Location and Building

The congregation has received from the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Endowment two houses next to each other on Enana Venus Street, Ankawa 108 District, free of charge. The house on the right is used as an official assembly location for rituals, the other as a cultural center for group meetings and administration. Like the neighboring houses, which are private houses of a high standard, the building has two floors, balconies, and a wall protecting it from street noise.

The building on the right can be recognized from the street by a front sign displaying the Mandaean symbol, the dravscha (flag in English): A cross with a white cloth[1] hanging from the horizontal arms. The inscription below says Manda Al Sabi’a Al Mandaeen (the Temple of the Mandaean Sabians). The same symbol is also carved into the main portal.[2]

After passing through a narrow front garden, the visitor enters a lobby that leads straight to a convention room. It is illuminated by ceiling lights and furnished with sofas along each wall, with low coffee tables between seats and two rows of chairs in the center. The room can accommodate about 70 people.

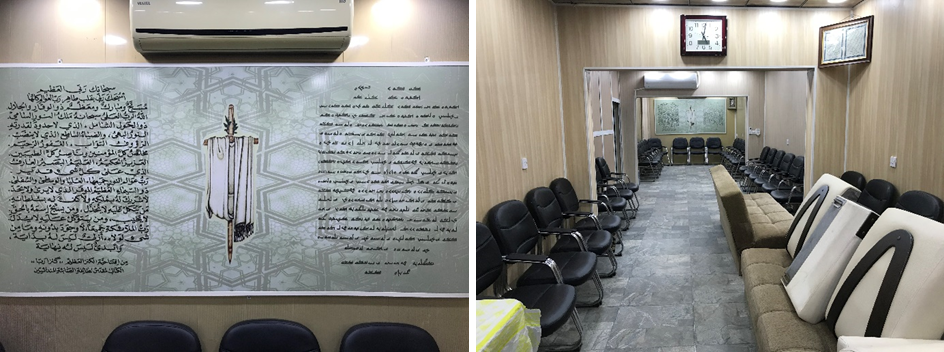

A second rectangular room is for liturgical use. At the front, a poster shows the dravsha (the flag) between a verse from the opening of the Ginzâ Rabba in Arabic (on the left) and Mandaic (on the right).[3] Chairs along the walls can seat around 40 people. On the opposite side, steps lead into a water basin (or “yardna” for baptisms), measuring 4 meters by 3 meters. From three fountains in the walls – which are covered with natural stones – water falls into the basin; through an outlet in the basin, water drains outside the building. This is necessary because baptisms must take place in running waters.

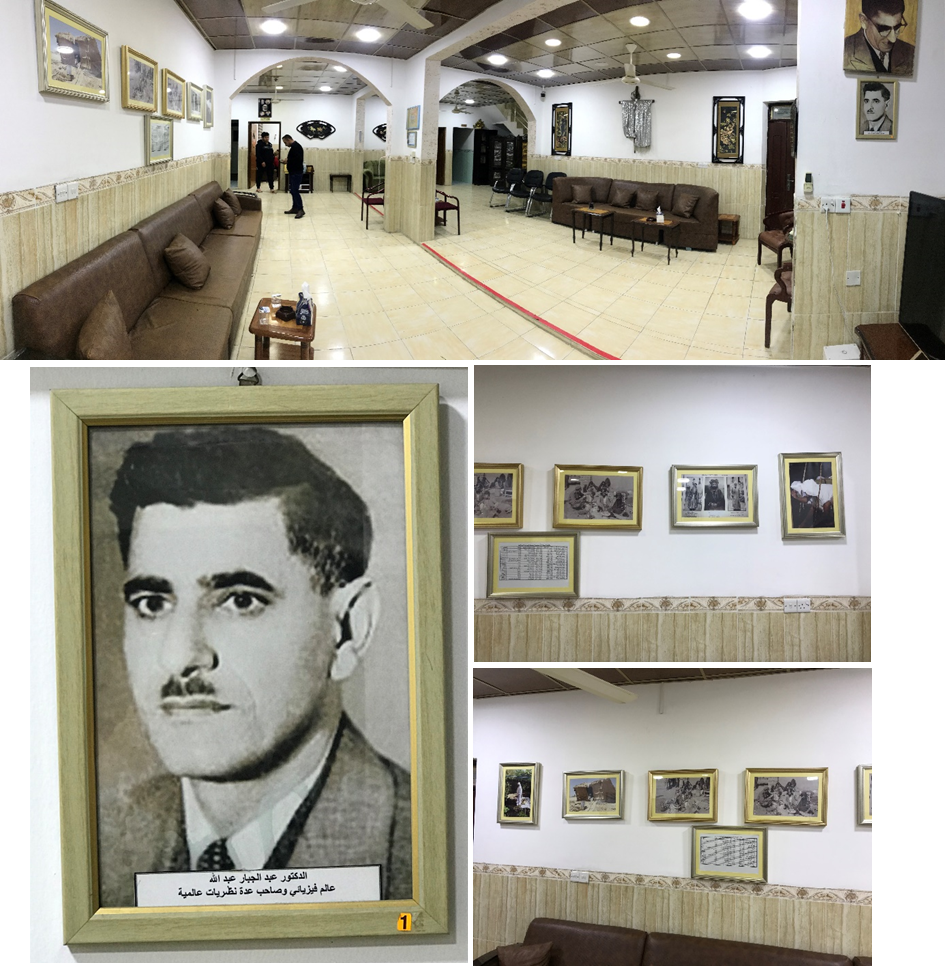

The adjacent building – same size and shape – is the cultural center. On the walls of the lobby, photos of famous Mandeans and traditional “mandi” (huts close to an artificial lake with flowing water) show the past and present of this religion.

Pictures on display inside the cultural center. The portrait at left is of Dr. Abdul Jabbar Abdullah, a Mandaean scientist and physics theorist.

[1] The cloth represents the vestments (“rasta”) of white cotton, which Mandaeans wear during the rituals.

[2] Khalid A. Roomi explained it as a cosmic symbol representing the four directions (cross), the cleansing of the human soul (cloth) and the blessing of God (grass sprouting from the wood). Interview with the chairman of the committee, Khalid A. Roomi, on November 12, 2020.

[3] This language is derived from ancient East-Aramaic and was established by an unknown linguistic innovator, probably in the second century CE.

Prayer and Worship

The maṣbûtâ (ceremony of immersion in water) is performed every Sunday at weddings, for women after giving birth, at the ordination of priests, and the consecration of a mandi (sacred house).[1] Due to the small number of Erbil’s congregation, religious rituals are not practiced weekly. Rather, religious persons are summoned from outside of Erbil only on specific occasions, such as weddings, feasts, and other occasions. On those occasions, approximately 60 to 70 participants are present in Erbil.[2]

The Mandaeans have four main festivals and two fasts: Dihwa Rabba (New Year’s Festival), Dihwa Hnina (Festival of Flowers), Bronaia (known as Banya, Festival of Creation), and Dihwa id Dimana (Festival of Adam’s Baptism). These are the main festivals in the Mandaean calendar. About 100 to 150 people participate in the main festivals. Banya or Bronaia is considered the most important festival in the year, which the Mandaeans believe is the time when God created the world of light. This festival lasts for five days, from March 17 to March 21, during which day and night celebrations are held, with night celebrations being forbidden.[3]

The two fasts are Soma Rabba and Soma Hanina. Soma Rabba (the major fast), which is the abstinence from any conduct that corrupts the relation between God and man, extends throughout the whole life of the Mandaean.[4] Soma Hanina (the minor fast) is intended to remind people of the Soma Rabba. In addition to the rules of the major fast, the minor fast includes abstaining from all animal products, such as from cattle, sheep and goats. The minor fast lasts a total of 36 days, spread arbitrarily throughout the year. Funerals are supposed to last seven days, but due to the obligations and costs involved, the duration of the funeral is reduced to three days. It is believed that the logic behind this practice is to reconnect the soul with its pneumatic body. After the funeral, people usually gather in a hall and are served coffee. For those who want to serve lunch to the guests, there is only one option, which is fish.[5] Fish is allowed because it does not have to be slaughtered, unlike other animals such as poultry and sheep.[6]

[1] Majella Franzmann, “Mandäismus,” Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 4th ed.), Vol. 5, 725-728:727.

[2] Personal interview with Ms. Faiza, a Sabi activist and the director of the Cultural Center, on November 12, 2020.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Al Sabia Al Mandaean: Haqa’q Rohya wa Ta’rikheyya” (The Sabia Mandaean: Spiritual and Historical Facts), translated brochure, 2017.

[5]Personal interview with Ms. Faiza, a Sabi activist, on 12th November 2020.

[6] https://www.ssrcaw.org/ar/print.art.asp?aid=176326&ac=2

Community and Group Activities

In 2019, about 600 Mandaeans lived in Erbil; 90% of them also worked there. The migration to Kurdistan continues due to the constant harassment by Muslims, but many Mandaeans have to stay in Iraq because they are employed by the government and would lose their jobs.

The younger generation is very loyal to the traditions of the older generation, but the community is shrinking for two reasons. The first reason is mainly related to “closed religions.” When a member marries a non-Mandaean – and this is very likely with minority religions – he or she “loses her/his religion,” leading to a steady decline in the Mandaean community. Secondly, the Mandaeans have suffered numerous persecutions by the majority religions.

The community goes to the river Greater Zab, about 32.30 km (20 miles) from the center of Erbil, where baptismal rites are performed.

For this reason, the leader – either from outside the country or from the southern communities of Iraq – comes a few times a year, chiefly for the main festivals. He knows the rituals and the sacred language.

The Sabi clergy are divided into five positions. The Halali (1) is the religious person whose duties are limited to leading funeral rites and performing battle rituals for the public. If the Halali memorizes the holy books Sidra Dnishmatha (the book of souls) and Nayani (the book of prayers) and stays awake for 7 days, he is promoted to a higher position called Tarmitha (2). In addition to the Halali’s duties, Tarmitha is authorized to perform marriage rituals. Tarmida is followed by another higher rank, the Ginzabra (3). Promotion to Ginzabra requires that the Tarmitha has memorized the sacred Ginza-rabba book and is thus able to interpret it. The highest rank that Sabi clergy currently hold is Rish-Amma (4). This position requires a person of great experience and can be attained if the Kanzabra has already ordained seven clerics. The highest rank among the Mandaean clergy is Rabbani. So far, no one has reached this rank except Yahya bin Zakariya. It is also important to note that this position cannot be held by two people at the same time. Rabbani is expected to live in the world of light, accept religious teachings, and then return to his own world.

Public Relations

Today, the Mandaeans – along with Christians and Yezidis – are granted “full religious rights for all persons and freedom of belief and religious practice” in the Iraqi constitution (Article 2). They are among the eight registered and protected religions in Kurdistan, as mentioned in Law No. 5 of 2015, which deals with the protection of ethnic and religious groups in the Kurdistan Regional Government. The Minister of Religious Affairs is well informed about this religion.

The ministry distributes a brochure that highlights the similarities with Christianity and Islam: John the Baptist, fasting, almsgiving, and morality (no adultery, stealing, lying, magic, alcohol, usury, divorce, abortion, or suicide).[1]

The Erbil community is connected with other Mandaean communities in Iraq. They meet annually for conferences to promote cooperation among Mandaeans in Iraq. Their relations with Mandaeans in the diaspora are also continuous. International conferences with the communities in the Diaspora used to be held every four years, but due to the current economic conditions and crisis, and lack of support, these conferences with the Diaspora are no longer held.

[1] “Mandean Sabians,” Erbil 2016, 6.